If you’re like so many practitioners I’ve worked with, in the beginning, you probably did what I did: I got more training. As often as I could.

That helped my knowledge base grow.

And because I’d taken the steps I told you about in my free course, How I Found the Confidence to Charge, and at least I had enough clients to use what I was learning in those advanced training programs, my confidence was gradually increasing.

But my practice wasn’t the one I’d daydreamed about as I lay on the floor in San Francisco during my training. Instead, it felt like an ongoing struggle.

Maybe you’re in the same place. You know you have what it takes but feel like the best-kept secret in town.

Why is that?

Is it a joke or is it the truth?

One day during the San Francisco training, Moshe Feldenkrais said that when something goes wrong, the most important thing is to figure out who to blame.

One day during the San Francisco training, Moshe Feldenkrais said that when something goes wrong, the most important thing is to figure out who to blame.

Maybe he was joking, or maybe he was simply telling us what he saw people do when things don’t turn out as they hoped. He often said things that were calculated to make us think for ourselves…

When I first graduated, I was living in British Columbia, Canada. At that time, most medical expenses in BC were covered by tax revenues—so, when I had an operation in my late 20s that put me in the hospital for 4 days, my bill for the entire adventure was a whopping $16.

Canadian.

About $12 in US funds.

Well, I mean really… as my confidence grew but my client base remained way too small, who could ask for a better scapegoat than the Provincial Medical Services Plan?

Blame is like the release valve on a pressure cooker so it’s really an excellent “go-to” when something goes wrong. Blame insurance. Or the economy. Or the fact that your modality isn’t well-known. Or that your family is still undermining your efforts by asking when you’re going to get a “real job.”

There are so many places to look if you need to blame someone or something other than yourself that you could live a lifetime taking no responsibility for anything that happens to you.

The only thing wrong with blame is that you end up feeling like a victim instead of an expert who can help other people.

Oh yeah… and one more thing… blame is a terrible strategy for attracting and enrolling clients.

How long does it take when you do it the hard way?

After a few years, I moved back to Washington DC, where I spent more than a decade working on building a Feldenkrais practice that I could rely on for support.

It was 1989 and I’d been a practitioner for 12 years, and an assistant trainer for 6 years. I was working with clients about 20 hours a week, and in that time, I saw 24 people privately and taught 3 classes. I had a good practice and I was really happy with it.

I was married with a toddler and a baby on the way and we were thinking about moving to Morgantown, WV because it would be a better place to bring up our kids.

I think I was in a haze of something like the amnesia that follows childbirth—it makes you forget the labor that preceded it. In considering the move, it never occurred to me to think about how much effort it had been and how long it had taken to build my practice relying only on my modality skills. Turns out amnesia is great for bonding with a newborn, not so great for considering a move that means you’re starting over.

Instead, what I thought about was that I had a successful practice and that meant that I was a good practitioner. And—as the myth promised, if I were a good practitioner, people would come.

So, I adopted the easy belief that if I did it once, I could do it again. And much faster this time because I knew I was a much better practitioner than I had been at the start.

Morgantown had a population was about 28,000 at the time. A far cry from the 600,000 people in DC (and over 3 million in the metro area), but certainly enough people to build a healthy practice—if only I’d known how to do it.

Sadly, I didn’t, so I relied on what I’d done before.

I posted flyers at the food coop about how great my modality was.

I tried to talk to doctors about how great my modality was.

I gave talks and free presentations about how great my modality was.

When anyone asked “What do you do?” I said, “I’m a Feldenkrais practitioner.” Then they said, “What’s that?” and I told them how great my modality was.

You can guess where this is going: I struggled to get my practice off the ground. More former clients came to me from 300 or 400 miles away than new people who lived locally.

I cobbled together a living by traveling.

I told myself that people where I lived just didn’t want what I offered.

By 1991, I was also a trainer and teaching in training programs in the US, Europe, and the Pacific Rim. In every place I taught, I met colleagues whose stories echoed my own: even though they had experience and knew at some level that they were good enough, they didn’t have enough clients.

“Why?” I asked.

They told me it was about the economy, the culture, the fact that our work wasn’t known and our guilds didn’t advertise enough, insurance… and often about the clients who didn’t come: people want to be fixed rather than take responsibility for their own well-being.

In 1999, I moved. Again.

This time to a small town in California with a population less than half of Morgantown, and where it seemed like every fourth person was a holistic practitioner, and guess what?

I was still struggling.

Even though by now, I’d been a trainer for nearly 10 years, had been teaching training programs around the world, had loads of case studies that told me I had no reason to doubt my ability as a practitioner.

Nobody had to tell me I was good enough. I knew it in my bones.

I couldn’t see the bigger picture

Looking back on it, I can see how limited my view of the situation was, but at the time, all I could pay attention to was how desperate I felt.

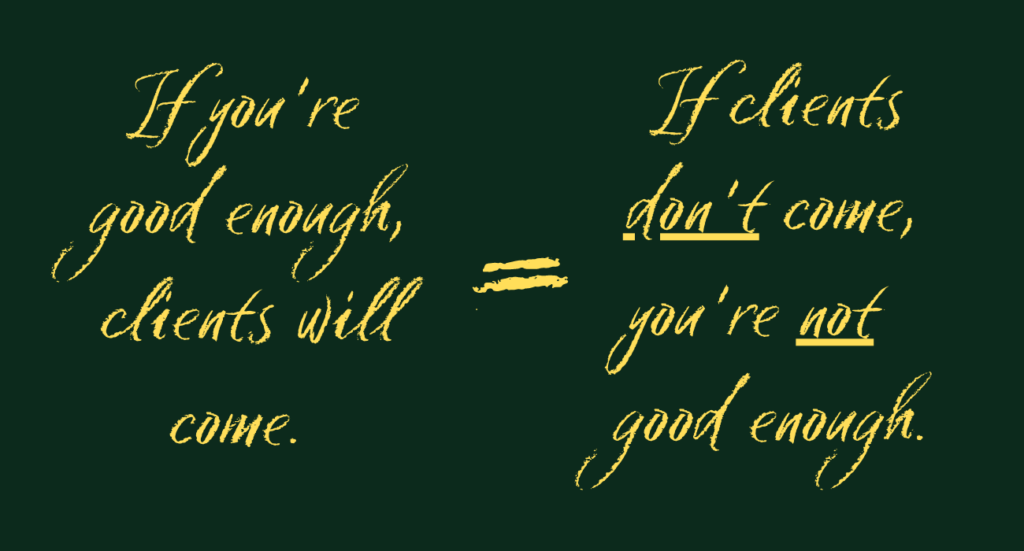

I was starting to wonder about the myth that equates your skill level to your number of clients in a way that can make it very hard to build a practice:

By now, I’d repeatedly proven to myself that I was good enough and I wasn’t tempted to fall down that hole again.

But where were my clients?

And who was responsible for the fact that they weren’t coming?

What obstacles are in your way?

When I first began to work with practitioners to help them build a practice, I created a short program called Align Your Mindset. It helped practitioners prepare for the work of learning how to get more clients.

Align Your Mindset focuses on how to deal with 5 common internal roadblocks that make your inner voices so loud you can’t think straight.

One of those is OBSTACLES… the blame-worthy factors that are responsible for our lack of clients.

Register below to access that short training—it’s FREE and in 10-15 minutes, you’ll have a bigger picture of what you can do to expand your practice, starting right now.

[If you don’t see the form, please REFRESH the page… that should make it appear. You may have to do it a couple of times because the company that form comes form hasn’t fixed the glitch yet.]