This is the first in a series of in-depth articles about why it’s so hard to get people to want Feldenkrais work, and what you can do about it if you would rather help people transform their lives than fix them.

If you spend any time at all reading social posts in groups whose members are Feldenkrais® practitioners, I’m sure you’ve seen comments along these lines…

-

-

- I gave a new client a great lesson. I could see how much she changed, and she told me she felt better. But she didn’t get it—at the end, she asked me for exercises she could do at home, and when I tried to explain that Feldenkrais is really about, she just looked blank and didn’t make another appointment. It feels like convincing people is so hard.

- I feel so down. I did some of my best work today with a new client and in the end, what emerged is that he just wants to be fixed. I wish I could get clients who want what our work is really about.

- What’s wrong with people? All they want is to be “done to.” I want clients who want to change the way they are in the world, people who want to learn, people who take responsibility for themselves. Where the heck are they?

-

It’s a commonly-held truth in Feldenkrais circles that our work is not about the vehicle we use to teach it… while it may look like it’s about the movement, that’s because—as Moshe himself famously said—

A brain without a body could not think.

And therein lies the rub

For most practitioners, everything “our method” relies on for “what we do” with our clients involves the body.

(I say “most” because as Moshe himself said, it’s possible to teach the same thing through other vehicles, but practitioners tend to stick with what they learned in their training, and that was about helping others physically.)

It’s no wonder Moshe chose movement as the vehicle for his message, from the 1940’s when he first thought about it, right through training programs in Tel Aviv, San Francisco (where I trained), and Amherst, where he opened a training with a whopping 250 on the floor who were all eager to make him “their last teacher.”

Not only did he have significant issues with movement himself, but he also recognized that one thing humanity shares is movement, or as we love to quote:

Movement is life. Without movement, life is unthinkable.

Moshe was a realist: If you want to change the way people think, choose a way of doing it that applies to everyone on the planet. I think he got about as basic as “universally human” can be.

It’s no wonder that for decades, Feldenkrais training programs focused on tuning awareness of what’s happening when we move, zeroing in on the nuance of muscular sensation, refining touch, and seeing life, volition, and achievement through the lens of gravity.

Transformation? Okay, sure, that’s what it’s ultimately about, but right now, let’s look at the ATM we just did and understand what it has to do with proximal and distal movement, and then we’ll figure out how we could turn it into a private lesson.

It’s no wonder that so many social media posts from Feldenkrais practitioners highlight the extraordinary in every realm of movement: sports, the arts, dance, theater, aging in exceptional ways, advancements in brain science. We love to share articles, videos, and TED talks about brain injuries, neuroplasticity, people who have exceptional physical abilities or who have excelled despite physical challenges.

Maybe it’s not a stretch to say that for the vast majority of practitioners “Movement is life, and paying attention to it gives meaning to MY life.”

So really—are you honestly all that surprised when somehow… it seems that movement overshadows the real intent of the work that transformed your life?

Truth, or Truth-Bomb?

Moshe told us that one important wellspring for his work was the realization that sometimes in psychotherapy, people got better… and sometimes they didn’t.

That was enough to launch him on a quest to find out “WHY?”

What he discovered was that successful psychotherapy was accompanied by physical changes. When those physical changes didn’t occur, neither did the psychological transformation.

As you would expect, he then walked around to the other side of the problem and asked himself a question: Could focusing on the body and creating conditions in which the physical changes occurred precipitate psychological shifts—without the need for years of therapy? Was it possible to stop reliving trauma in order to understand it—and get the same result without experiencing the emotional pain that almost inevitably accompanied the psychotherapeutic process?

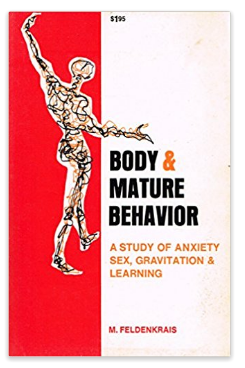

He summed up that inquiry in the dense volume, Body and Mature Behavior: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation, and Learning.

It was my first introduction to Moshe-in-print and I dove in with enthusiasm just before attending the first summer of the San Francisco training in 1975. To be honest, I didn’t understand 3 words in a row when I first read it. But imagine my amazement when I read it again in the autumn of that same year and wondered to myself… What was so difficult about this book last spring?

It didn’t occur to me until some time later that he had taught every concept in the book while we all were lying on the floor. Little wonder that it made sense cerebrally after experiencing it somatically.

Moshe wanted to help us all develop the fullness of our human potential. To him, that meant challenging much of what we think we know, and especially what we think we know about how to think.

On the one hand, choosing movement as the vehicle for that learning was obvious, because he was convinced that what we held in our musculature kept us prisoner in our thoughts, feelings, attitudes, responses, and behaviors. But it was also genius—or great good fortune—because at the time he was most active, the world was starting to wake up! It was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. We were seeking, looking for experiences, intentionally trying to expand consciousness.

What better laboratory for that than our own bodies? We didn’t need special clothes or expensive equipment. We didn’t need sherpas to guide us to mountaintop-gurus or training to breathe the rarefied air there. The most important thing we needed—gravity—was inescapable anyway, so it was totally easy:

Lie down and you’re ready to go. Or sit. Or stand. Or kneel. It doesn’t really matter because you can learn from everything you do.

It was brilliant.

Truth or Truthbomb?

To an outside observer, I’m sure that it looked—and still does look—a lot like changing something physical. Changing something physical relies on the body. People who work with the body are body-workers.

Personally, I think it’s both the truth and a truth-bomb.

Because that’s the kind of world we live in: one where information is so abundant, and where the number of messages bombarding us on a daily basis verges on the unimaginable. There is so little time to think deeply.

In today’s world, I know it’s still possible to distinguish Feldenkrais from bodywork—I know that you and I can make endless distinctions about how our work is not really like any other modality, does not really focus on the body, and is not really about movement… but to the vast majority of people who don’t have—or won’t take—the time and haven’t had the training we’ve had, it looks a lot like bodywork.

How did that happen?

Think about any news article you’ve seen about the Feldenkrais Method written by someone recently acquainted with the phrase “Please lie on your back.” I’m willing to bet that you ended up wishing you could correct the basic misunderstanding under which the writer labored.

Listen to your clients describe what you do and more than likely you’ll hear them say things that will leave you shaking your head and wondering how they got those ideas from what you did with them.

Bring your tissues when you look on Wikipedia to see what it has to say about the Feldenkrais Method. It’s especially disappointing to read articles written by people who are trying to be helpful without really knowing what our work is about.

But that misunderstanding is so logical…

On any given day, you help people who have physical problems. Usually, that involves touching their bodies in some way. Even if you don’t have Functional Integration clients, a casual observer would likely say that ATM also looks like it’s focused on the body.

Your training focused heavily on touching people. Very likely, your trainers went to great lengths to make a distinction between “Feldenkrais” touch and anything else you knew before you arrived—or would ever learn in the rest of your life.

This distinction is a lot like the elephant test—hard to describe, but you know it as soon as you see it… or feel it. Your trainers let you know that they could see and feel it, and you know they expected you to be able to see and feel it, as well… because after all, it isn’t really about the movement.

How did you learn to do that?

Ask yourself, “How long did it take you to ‘know it when you see it?'”

Ask yourself if, anywhere along the way, you might have thought another modality looked like it might be Feldenkrais.

Ask yourself if maybe you saw, received or gave a lesson that you knew was Feldenkrais, but could have been mistaken for another modality by an observer with less training than you have.

Maybe you saw an image on Facebook that looked like Feldenkrais, but on reading the post, it turned out to be something else.

Or maybe you were sure that image looked like something else and you were astonished to see that it was Feldenkrais. It was even taught by someone whose name is familiar to you.

The irony is that the universal application of our work is one of the things that makes it so difficult to understand. In choosing movement and physical action as the vehicle for learning, Moshe picked the easiest way to communicate the process and bring about the changes that people need—during my training, his dream was to be on Telstar, teaching ATM to people all over the world at the same time.

But our focus on movement and touch is so powerful—and so well-based on principles of science that Moshe could easily reference—that it can obscure the deeper meaning which takes many people an entire training program to understand.

This is one of the primary reasons that it’s much easier for people to connect to YOU around the changes they feel, than to a deeper understanding of what actually happened to them.

That’s why what you take for granted—now that you know it and can spot it immediately—is something that probably took you much longer to grasp than many of your potential clients have spent finding you.

It’s unreasonable to expect people to grasp the depth of what you know before they even know who you are or what you do.

Even if they know something about your modality, most people are not thinking about transformation. They cannot know before they meet you whether there is even hope that they can go where they think they want to go … let alone what else is possible for them. Practitioners often tell me it takes 5 to 8 Functional Integration sessiions before their clients start to “get it.”

The irony is that as soon as people become clients, we show up exactly as the person most folks hope we will be when we first meet them!

It’s not even hard—it’s a fundamental aspect of the Feldenkrais Method! We simply need to apply it from the start:

Meet people where they are. Help them get where they want to go. Show them how to keep on going.

Next time, we’ll explore what this means in practical terms.

To make sure you don’t miss it, subscribe here.